Sukeban - The Forgotten Story of Japan's Girl Gangs

Available from: https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/28261/1/remembering-japans-badass-70s-schoolgirl-gangs

Thumbnail Photo Available from: https://www.vintag.es/2018/10/sukeban.html

By Hannah Schmidt-Rees

The sukeban was a truly unique subculture in Japanese society, one that unfortunately has been forgotten and its original purpose changed. The term 'sukeban' was created by Japanese police to categorise and explain the rise of teenage all-female street gangs in the 1960s. Meaning 'delinquent girl' or 'girl boss', the sukeban were groups of teenage girls that protested against society with their altered fashion, radical solidarity and being involved in offences such as, violence, theft and drug use. But these gangs of rebel girls used their actions and their fashion to prove that being strong and being a woman wasn't contradictory.

They protested against mainstream gender norms and feminine expectations in a male-dominated society. The idea of a woman 'behaving badly' went against the gender norms of how a woman is supposed to act, and provided a thrilling way to challenge society. In addition, the expectations of how a woman dressed were restricting and sexist, and the sukeban weren't going to accept this anymore.

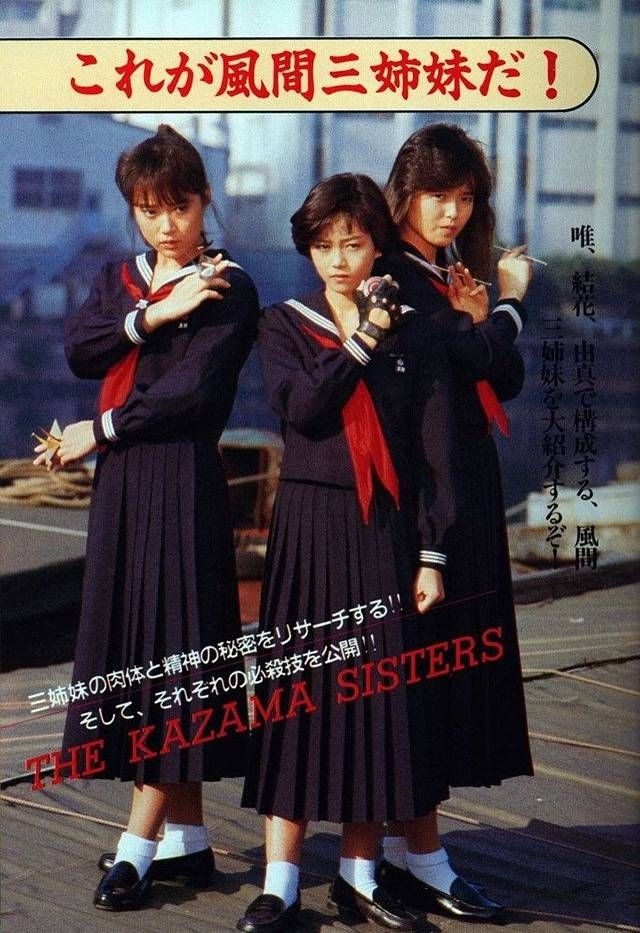

The main motif of the sukeban started with their school uniforms. The western sailor-style uniforms were seen as an unwanted and restricting symbol of tradition. Popularised by the education system in the early 20th century, these sailor-style seifuku uniforms became unwanted by the young girls of Japan in the turbulent 1970s.

Available from: https://www.vintag.es/2018/10/sukeban.html

By the early 1970's, the sukeban began to create their own memorable aesthetic by modifying their school uniforms. Sleeves were rolled up, hair was dyed bold colours, school shoes were replaced with Converse sneakers, skirt lengths were increased and blouses were cut short to expose the waist. Even after members of the sukeban graduated, they continued to wear their uniforms and would customise them even further; embroidering roses and anarchic kanji characters and gang symbols into their blouses - a motif that doesn’t seem too different from the customisation trend of the British punk movement (which you can read about here).

But the sukeban weren't just a group of girls with an interest in looking a bit edgy, they served as a worthy rival to their male equivalents. In every fashion movement, aesthetic is inherently linked with function. The layering of the school uniform provided perfect opportunity to conceal weapons; knives, razors, and chains. Sukeban groups faced off with rival factions, punished girls in their own groups and participated in their fair share of petty crime in their local community. The largest sukeban group had over 20,000 girls (larger than some Yakuza groups at the time), so these customised uniforms meant business.

Like I said before; 'these gangs of rebel girls used their actions and their fashion to prove that being strong and being a woman wasn't contradictory.' Despite the petty crime, the sukeban believed that women should be brought to the forefront of society and respected. The sexual revolution of the 1960s, whilst yes, was a revolution of women now being more in control of their sexuality, it also increased the idea of a woman's existence solely being for male pleasure. The altered and increased length of the sukeban's skirts could be seen as a protest to the sexual revolution (and the sexualisation of the Japanese schoolgirl uniform), they didn’t want to be seen as something to be desired by men.

The period of adolescence is a major stage in the formation of one's identity. It is also a period of great experimentation and self-expression. Wearing a school uniform imposes a set of societal expectations on an individual, which can conflict with one's need to be different. When an organisation wants you all to look the same, what provides a better adrenaline rush than breaking the rules and making your uniform a little different?

I remember my own high school experience, seeing people changing their uniform in little ways to feel a little different. Granted, they weren't as intense as the sukeban, but I loved seeing groups of girls with the same alternations walking around, like a gang in their own way. Rolling up sleeves of blouses, tucking their shirts into their skirts, cutting long hair into pixie cuts, wearing unmatching socks were all commonplace at my high school, to the dismay of the teachers. You wanna hear what I did with my uniform? It's not that crazy, but at the time I having a hard time with my gender identity. In a school where the girls were expected to wear skirts, I wore shorts everyday from Year 8 to Year 12. I rolled up my sleeves and I was also one of the only girls to cut my hair into a 'boys' undercut in Year 11. It was my way to express myself in a place that required everyone to look the same, a way to explore my gender identity and feel unique while doing it.

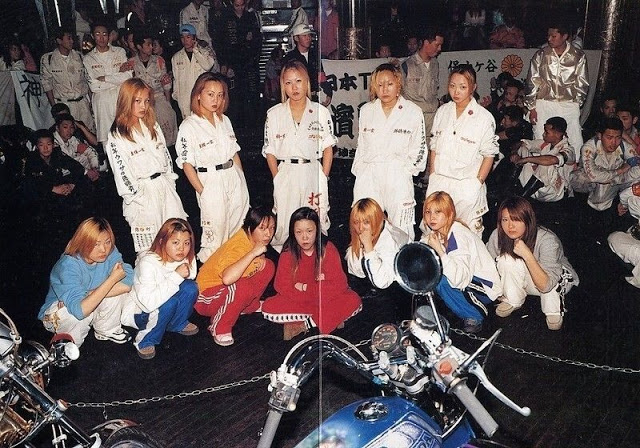

A bosozoku gang. Available from: https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/28261/1/remembering-japans-badass-70s-schoolgirl-gangs

By reaching pop culture fame in 1980s, the sukeban became popular characters in Japanese films (the most notabledirected by Norifumi Suzuki), television series (check out the Terrifying Girl's High School series) and manga. Even the original design of Makoto Kino (Sailor Jupiter from Sailor Moon) imagined her leading a sukeban gang. At that time, the original sukeban of the 1970s had grown up and settled into 'normal' lives, leaving only the pop culture sukeban trope to inspire Japanese society. Unfortunately, due to pop cultures influence, the traits of the sukeban, their strength, solidarity and protest turned into a sexualised trope for young men's enjoyment (sukeban were commonly featured in seinen manga, a genre marketed towards young men) and original evidence of the sukeban was slowly overtaken and forgotten.

Regardless of the end of the original sukeban, their impact is still seen in Japanese society. The expectations of young Japanese women to marry and settle down still prevails, but the subculture of all-female gangs provide women with a different life to embrace. The bosozoku, all-female biker gangs emerged after the girlfriends of male biker gang member grew tired of being at the back of the bike. Much like the sukeban, the bosozoku can be identified by their embroidered jumpsuits, rose tattoos and embellished bikes. The life of a sukeban was a life where a women does not have to bow down to a man, and the customisation of fashion wasn't just personal preference, it was to protest against the societal standards put against them.