20 Minutes into the Future - Max Headroom

By Hannah Schmidt-Rees

The thing is, I never really knew about Max Headroom until a few days ago. Granted, I have known of Max Headroom for a couple years now, and until a few days ago, I just dismissed him as weird 1980s character. Turns out he’s a bit more than that.

Max Headroom began as a computer-generated artificial intelligence video jockey.

In the early 1980s, producer Peter Wagg was contacted by British TV network, Channel 4, who were in need of small programming slots for a upcoming music video show Think of the original MTV, the small guidance scenes in between the music videos, presented by a television personality. Wagg looked at MTV for reference, which had originated the concept in 1981, and decided that the video jockey didn’t need to be a real person, he could be animated.

Wagg contacted writer George Stone to join his team, and the first thing that was agreed on was the name; Max Headroom. In 1980s Britain, the height restriction signs that we know as “Max. Height” were originally “Max. Headroom”. It was piece of signage that everyone knew, easily recognisable and could act as a form of free marketing. But it also had another meaning; maximum headroom is filling your head full of sound and vision.

When it came to animation, Wagg reached out to Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel, who were cutting-edge animators at the time. When discussing the concept of an animated figure, Morton came up with “the most boring thing that [he] could think of to do, which would go against the grain for the MTV generation… was a talking a head: a middle-class white male in a suit, talking to them in a really boring way about music videos.” And the seed for Max Headroom was truly planted.

Matt Frewer

George Stone decided that he should be computer-generated, and from this point, an entire narrative began to unfold. This narrative was called “20 Minutes into the Future”, explaining how Max Headroom came to be. All this progress was made, but at this point, no-one whew what Max Headroom would even look like.

The team pitched it Channel 4, who liked the idea so much that they gave the opportunity for an hour-long film to set up the narrative before the real 13-part show aired.

By 1984, the idea had enough funding to get started. Unfortunately, the team fell out with George Stone due to creative conflict, but a replacement writer Steve Roberts took his place to write a final script for the film. At the same time, the hunt for Max Headroom, at least his actor, began. Matt Frewer, an American actor living in Britain decided to audition for the role by recommendation from a friend. His precasting photo immediately caught the eye of Jankel, who noticed his incredibly defined features. Frewer was called in for a 10-minute improvisation around six lines of Max Headroom dialogue, encouraged to riff like a weatherman or a newsman. Frewer and the creative team instantly hit it off.

“So what you have in the character is a consciousness — fully human, totally amnesiac — whose first experience to the world is exposure to 30,000 simultaneous channels of television. That’s where the character comes from. He is a fusion of every evangelist, every sports reporter, everything you see on TV. And from his perspective he sees no difference or distinction between them.”

After 10 minutes, Max Headroom was found. But the question, still remained, what would he look like? He was going to be a computer generated character after all.

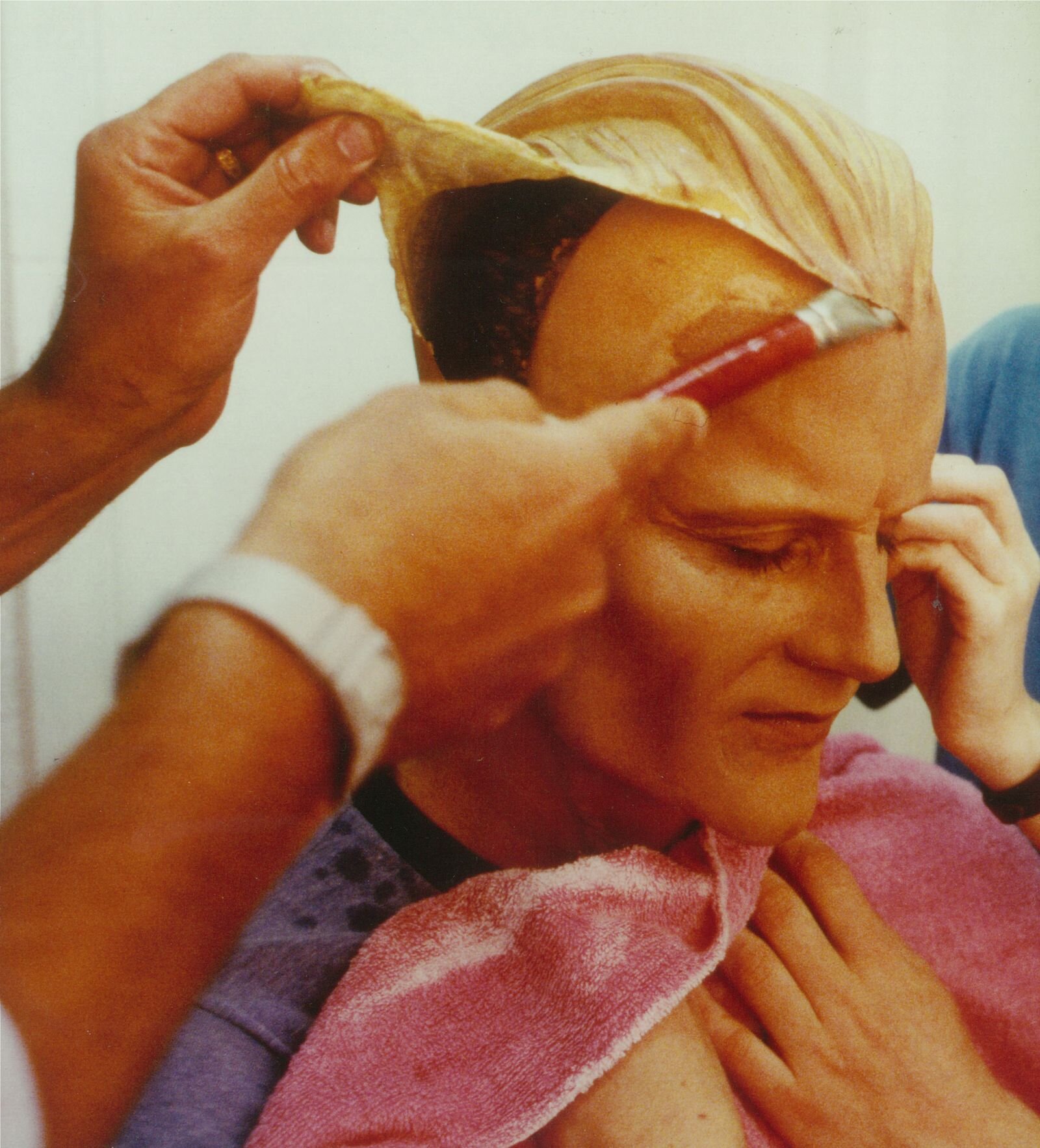

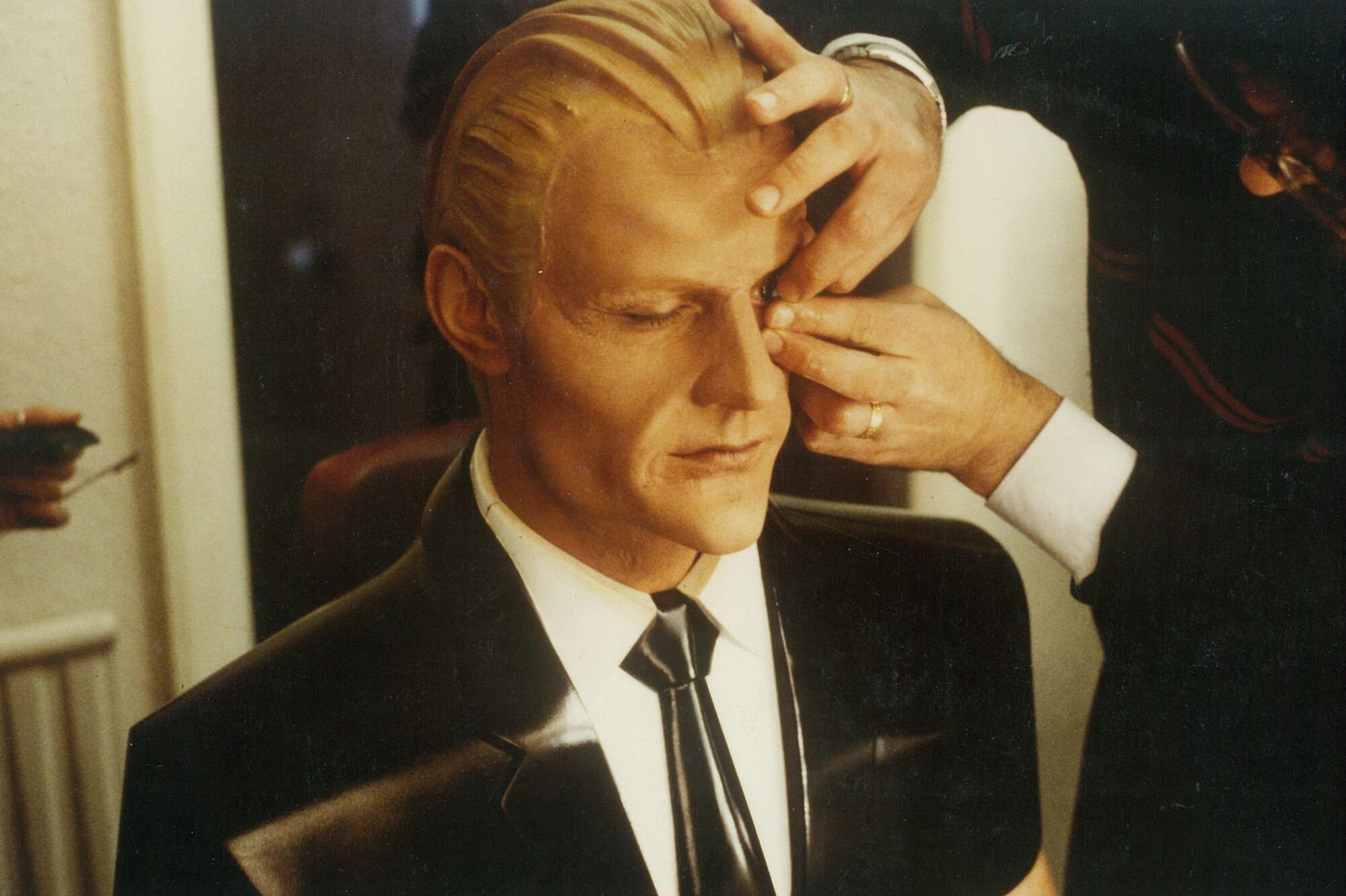

Jankel and Morton experimented with computer graphics and 2D animation, ultimately realising that what they wanted was years down the line. Morton states; “[It’s] the face. The human face. We’ll just use the actors face and just make it appear as if it was computer-generated by putting prosthetic make-up on it, and then shooting it in a certain way; we could make it look like it’s computer-generated."

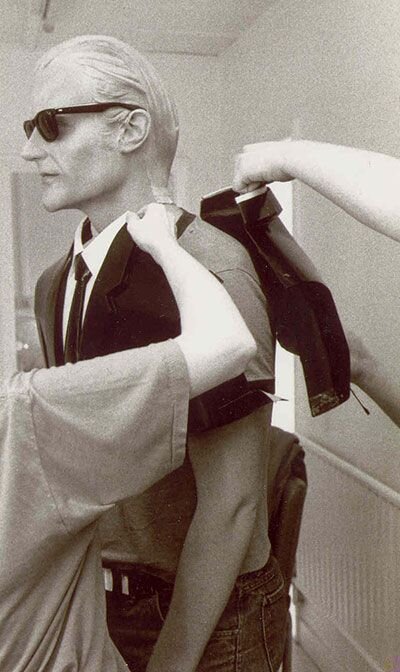

Prosthetic prototypes were created, but the problem was, what does a computer-generated TV presenter look like? Max was the first of his kind, so it was decided that Frewer’s features would simply be accentuated, not fully covering up his expressive nature. His suit, made to look artificial, was two fibreglass pieces, screwed together on Frewer’s shoulders. The now iconic linear backgrounds were taken from a flavoured milk commercial that Morton worked on. Frewer were placed in front of a blue screen, dramatically lit from one side, and finally Max Headroom was ‘physically’ born.

“20 Minutes into the Future” was an example of the visual zeitgeist at the time. Set in a near-future, post-punk dystopian future, TV networks have a strong hold on society. Network 23 has created a form of subliminal advertising (called ‘blipverts’), compressing 30 seconds of advertising into 3 seconds. However, blipverts can be fatal to some viewers, but the network doesn’t care as long as they get the ratings.

Popular journalist Edison Carter decides to bring the truth of the blipverts to the public, but in his attempt to flee the Network 23 headquarters, Carter suffers a serious head injury by hitting a “Max. Headroom 2.3m” sign. In order to ensure the public doesn’t notice Carter’s disappearance, Network 23 uploads his consciousness to the digital space to be used a temporary replacement. The programming proves unsuccessful, as Carter mumbles gibberish and ‘max headroom’ over and over, and Carter both digital and physical are disposed of. The failed program falls into the hands of ‘Blank Reg’ a punk video jockey and owner of a pirate television station. Reg brings the program to life and the mysterious personality, now calling himself Max Headroom takes the place of the station’s tv host, sending Reg’s rating through the roof. Physical Carter escapes from near death and returns to journalism, working with Max Headroom (who appears on TV screens) to finally defeat Network 23’s and their blipverts.

I’ve seen “20 Minutes into the Future” and I love it. Every piece that I knew about Max fell into a place with this film, and I feel that I understand his entire character from this film. It has some elements similar to Bladerunner, The Matrix, even Metropolis; with unique costuming, graphics (which were made by a Commodore 64) and staging; creating this incredible aesthetic and attention-grabbing possible timeline.

The film aired to great success, and three days later the original concept, the music-video show aired. When the show began, there were no credits, simply static until Max appeared. The classic Max Headroom dialogue ‘introduced’ each music video, with the show finally ending with more static. Frewer’s performance was stuttered, looped and artificially changed, to create an effect of computer jamming. As a character, Max was incredibly meta, aware of who he was as a character, the capitalist nature of TV and the possible dystopian future.

After three weeks, the ratings doubled. The show even won a BAFTA for graphics, even refusing to be entered into the make-up category to keep the secret that Max wasn’t really computer-generated.

“Anybody under the age of 25 just loved it. And anybody above that age was just completely confused. It was amazing, you know. It was a genuine phenomenon in its time.”

The creative team knew that the short segments between music videos wouldn’t last, so in the final episode Max interviewed British artist Sting about his first solo album. The show slowly transformed into a bizarre talk show. Pop stars could promote their latest work in exchange by getting roasted by Max. The even had a live audience at one point. Max a had become a breakout icon, and a slew of merchandise followed.

The thing was, Max was a computer-generated AI character, appearing in television screens. He could anywhere and anytime, in multiple different contexts. The possibilities for Max, this charismatic, unique and satirical character, were endless.

By 1986, Coca-Cola needed a spokesperson to promote their new product reformulation; New Coke, which was quickly failing. Max Headroom was seen as the perfect fix. For three years, Max became the spokesperson for New Coke, with Ridley Scott directing the commercials. Max had now become a mainstream global phenomenon. Every major company now involved with Max Headroom wanted to continue pumping out content. He was featured in the song ‘Paranoimia’ by Art of Music, appearaned on trading cards, sleeping bags, watches and even has his own game for the Commodore 64, all in 1986. The original creators, Morton and Jankel wanted to keep control over the intellectual property, but after the effect of legal costs, they eventually they lost the control.

“20 Minutes into the Future” was remade into an American TV series, further exploring the story of Edison Carter, Network 23 and Max Headroom. The first episode was an identical reshoot of the original British episode, replacing all but Carter/Headroom, Blank Reg and Theora (Carter’s co-worker/love interest) with American actors. After this first episode, ‘blipverts’ and the original creators (Jankel, Morton and Stone) were never mentioned again.

The show was a dystopian look into a future where television networks rule society, where people are simply ratings. The show in itself ran against the principles of the network it was created by. This show, while constantly over budget and full of production issues, brought in a major audience, once having ratings of 58 million.

In 1987, Max appeared on the cover of Newsweek. It was one of the highest points of Max’s career, but unfortunately is was one of the last. The talk show concept was revamped for America, called “The Original Max Talking Headroom Show” (which was filmed in front of a live audience and is the perfect capture of the 1980s zeitgeist, combined with Max’s meta and satirical humour), while “20 Minutes into the Future” was moved to a graveyard slot, performing against Miami Vice and Dallas, two incredibly popular shows at the time. The ratings slumped, and when combined with the high budget and production issues, the network pulled the plug during its second season.

Max Headroom ceased from everyone’s TV screens, but his unique legacy lives on. Unfortunately, the rights to Max Headroom are held fairly tightly, meaning that future works are nearly impossible and re-releases of the original shows are hard to find.

It’s easy for futuristic concepts and films/tv shows to fall out of time, as the future they predict eventually comes. The thing with Max Headroom, as he was so unique and presented such a weird view of the future, that this specific future probably will never come, ensuring that Max keeps this sense of timelessness. He was such a perfect capture of the 1980s, but was cutting edge for the 1980s, and he’s still cutting edge now. He’s obscure yet well-known, satirical yet truthful. Max presented a version of the future that we can all relate, in every era.

““Max is a character you can’t beat. He’s the clever innocent who keeps looking; he’s only a few hours old and so he has all this information, but he doesn’t have any knowledge. That character is always fun and timeless.” ”

It’s more like we’re “10 Minutes into the Future” instead, as we’re halfway there, but not quite there yet.

I’d also like to discuss this idea of Max inadvertently becoming something that he was originally against. The creation of Max was due to Edison Carter risking his life to reveal the terrible truths of Network 23 to the unknowing public. Carter was against the idea of television being reduced to something simply to advertise and make money, at the expense of the life and health of its viewers. When Max became the face of New Coke and appearance on various merchandise, it created a metaphorical double-edged sword. Max became the face of television advertising at the expense of his original values, but without this, it’s unlikely that Max would’ve had the success and the impact that he did. It goes to say that it was probably a good thing that Max’s TV career ended when it, as it stopped the probable further homogenisation of his character, simply being turned into a way to make money. It’s an interesting thing to think about.

I also think that I can’t write an article about Max Headroom without mentioning the 1987 Max Headroom signal hijacking. Two television stations were hijacked by a video of an unknown person wearing a Max Headroom mask and costume, talking with distorted audio. A panel of corrugated iron spun back and forth to mimic Max’s background. After 115 seconds, normal programming resumed and the culprit(s) were never caught. It’s considered one of the most well-known TV hijackings of all time.

(I’d like to give thanks to my Dad for first exposing me to Max Headroom a few years ago. I didn’t get what was so great about it then, but I definitely get it now. Thanks Dad!)